A well thought through project plan is a great tool for both planning your project work, and also for tracking your project work. It can help you to identify all the steps that need to happen to get you to the end of your project. As you work through the tasks the plan also lets you know if you are on track, or falling behind.

The plan can act as a roadmap for everyone who is working on your project, including yourself. But it can only act as a roadmap if it is available. If don’t publish your plan for others to see then you are not using the power of the plan to communicate to your team what the project is about. Think about what the plan holds: tasks, who is completing each task, how long the task should take, what is dependent on the task…A wealth of information that can make your role as a project manager much easier.

What do I mean by publish? Just making it visible. Print it out and stick it on a wall, somewhere where your team can see it and refer to it. You could email a soft copy to team members who work remotely.

Try publishing in different ways. For example you could post the schedule gantt chart view – this has the advantage of all team members seeing not only their own tasks but the tasks of others and the dependencies between them. Team members might also find it useful to get a list of all their tasks – a to do list.

If you’re running a project for yourself, with just you as a team member, you should still make sure that plan is somewhere where you can see it. Stick it on the fridge, or by the cookie jar – use it as a motivational tool for those moments when you might prefer to be doing something other than your project tasks. Put a reminder in your phone or calendar to review the plan regularly.

Reviewing the plan is the first step towards monitoring the success of your project.

Monday, December 13, 2010

Mitigate project risk

Mitigating a risk means to reduce the likelihood or impact of the risk, or to prevent the risk happening.

Working out the mitigation strategies gives you a backup plan that you can use should the risk occur. It means you are ready and don’t have to think through the problem when what you thought was a risk turns out to be a very real issue facing your project.

Let’s say your risk is that someone will call in sick, leave you short of people to run your project, and so delay your delivery. You could mitigate this risk by hiring temps to cover the absence, or maybe by making sure ahead of time that you have others who could step in, and making sure they are trained appropriately. In this example the risk could still occur, but you are more prepared and have options to reduce the impact.

If your risk was that you suspected a key supplier might not deliver vital supplies on time, you might mitigate the risk by working with another supplier. Or using two suppliers, or carrying more supplies in stock, or including penalty clauses in your contact with the vendor. In this case you are reducing the likelihood of the risk occurring.

You can see that there might be many ways of mitigating any one risk. Thinking through mitigation is an opportunity for you to think creatively.

Working out the mitigation can also mean you revise your original assessment of the risk. You might decide that the mitigation steps are sufficient to reduce the likelihood or severity of the risk so much that you are comfortable in reducing the score of the risk, and giving it less attention. Or, you might find few or no mitigation strategies, and so want to raise the score of the risk and keep it on your radar.

When you have identified your project risks you should review your project plan and determine if you want to make any changes. Do you need to add more contingency to any of your tasks? Do you need to add tasks you need to complete as part of your risk mitigation strategy? It might seem that you are making your plan more difficult to complete, but making your plan more realistic is a preferable option to ignoring risk and having it derail your project – that would be more expensive in the long run.

With your plan in place and risks identified you are close to being able to publish your plan.

Working out the mitigation strategies gives you a backup plan that you can use should the risk occur. It means you are ready and don’t have to think through the problem when what you thought was a risk turns out to be a very real issue facing your project.

Let’s say your risk is that someone will call in sick, leave you short of people to run your project, and so delay your delivery. You could mitigate this risk by hiring temps to cover the absence, or maybe by making sure ahead of time that you have others who could step in, and making sure they are trained appropriately. In this example the risk could still occur, but you are more prepared and have options to reduce the impact.

If your risk was that you suspected a key supplier might not deliver vital supplies on time, you might mitigate the risk by working with another supplier. Or using two suppliers, or carrying more supplies in stock, or including penalty clauses in your contact with the vendor. In this case you are reducing the likelihood of the risk occurring.

You can see that there might be many ways of mitigating any one risk. Thinking through mitigation is an opportunity for you to think creatively.

Working out the mitigation can also mean you revise your original assessment of the risk. You might decide that the mitigation steps are sufficient to reduce the likelihood or severity of the risk so much that you are comfortable in reducing the score of the risk, and giving it less attention. Or, you might find few or no mitigation strategies, and so want to raise the score of the risk and keep it on your radar.

When you have identified your project risks you should review your project plan and determine if you want to make any changes. Do you need to add more contingency to any of your tasks? Do you need to add tasks you need to complete as part of your risk mitigation strategy? It might seem that you are making your plan more difficult to complete, but making your plan more realistic is a preferable option to ignoring risk and having it derail your project – that would be more expensive in the long run.

With your plan in place and risks identified you are close to being able to publish your plan.

Saturday, December 4, 2010

Project Risk

With a draft plan in place you’re ready to start work – or are you? That draft plan is assuming that things will go to plan, and does not, for example, allow for

- tasks taking longer than anticipated

- new, necessary tasks being discovered,

- problems being encountered which need to be resolved

- supplies not being available on time

- or anything else that might go wrong.

Identifying risks allows you to think about ways to prevent those risks from happening, or reducing the impact of those risks. In other words, mitigating the risk, which means to reduce the likelihood or severity of the risk.

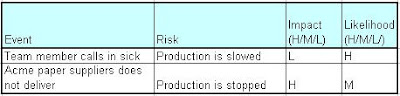

What does that mean? Let’s think about the first dimension of risk: likelihood. It might be feasible that your new manufacturing machinery might fail, but if you know it is new, it has warranty, and comes from a reliable vendor, then the risk might be identified as low in likelihood. But if you have experience of an unreliable vendor who provides supplies for your new project, you could rightly identify a likely risk of them again failing to deliver on time. Late delivery might mean you fail to meet your schedule.

The second dimension of risk is impact. Using the above example, if your machinery failed that could be a high impact risk – it would bring the whole production line to a halt, while you have workers standing idle, and deadlines not being met. Another example of one of those workers calling in sick one morning will not stop the whole production line, so might be a low impact risk.

Some risks you identify might not be relevant – you need to be realistic. A low-flying aircraft could crash into your factory, destroying it, and preventing you from manufacturing your new product. Although impact would be extremely high, the likelihood of this happening is very low indeed. So low you should not even consider it – it is not relevant to your project.

So, for each risk you identify you need to assign an impact and a likelihood, and you can create a risk matrix where you identify likelihood and impact as being either High, Medium or Low.

For projects that have many risks or where you need help working out which risks to worry about the most you might weight likelihood and impact with a score. For example assigning a value of 3 to High, 2 to Medium and 1 to Low, and multiplying out to get a total score for risk.

The risks with the highest scores are those you need to worry about – they are more likely to happen, and if they do happen they have a higher impact.

Next steps will be to work out how to mitigate the project risk.

Friday, July 30, 2010

Basic Project Management Definition # 3 - Gantt Chart

In some of the previous posts I’ve included pictures of Gantt charts like this one.

The Gantt chart is way of describing your chart visually, which will help you to schedule your project. Each task of your project is represented by a numbered horizontal row in the chart. And Time is represented along the top. The example above is showing weeks: you can see the start date of that week, each day represented by its initial letter, and each weekend represented by those vertical blue stripes.

On this framework you can then plot when your tasks will be completed and how long they will take. In the example you can see that the task “Prepare timber” will start on Tuesday August 3, and will take 3.5 days to complete, finishing on Friday August 6.

I’ve just used the column “Duration” to specify how long the task will take (more on this in later posts). In the example you can also see columns which show the start and end dates. I spoke about dependencies in the last post, and you can see these represented by the arrows between tasks: task 11 is dependent on the groups of tasks represented in rows 2 and 7.

This example was put together using a tool called MS Project which has way more functions and smarts than I’ve shown in this example, but you don’t need MSProject to plan with a Gantt chart. Some of the best and most useful charts I’ve seen have been thrown together on a whiteboard. I also use this format with pen and paper.

The Gantt chart helps you to visualise your project, and to question some of the assumptions round scheduling. Using this format is a also great way of communicating and sharing ideas about scheduling with others.

Wikipedia definition: Gantt chart

On this framework you can then plot when your tasks will be completed and how long they will take. In the example you can see that the task “Prepare timber” will start on Tuesday August 3, and will take 3.5 days to complete, finishing on Friday August 6.

I’ve just used the column “Duration” to specify how long the task will take (more on this in later posts). In the example you can also see columns which show the start and end dates. I spoke about dependencies in the last post, and you can see these represented by the arrows between tasks: task 11 is dependent on the groups of tasks represented in rows 2 and 7.

This example was put together using a tool called MS Project which has way more functions and smarts than I’ve shown in this example, but you don’t need MSProject to plan with a Gantt chart. Some of the best and most useful charts I’ve seen have been thrown together on a whiteboard. I also use this format with pen and paper.

The Gantt chart helps you to visualise your project, and to question some of the assumptions round scheduling. Using this format is a also great way of communicating and sharing ideas about scheduling with others.

Wikipedia definition: Gantt chart

Wednesday, July 28, 2010

Basic Project Management Definition # 2 – Project Dependencies

A second term which is important during your project planning is “Dependency”. If task B cannot start until task A is complete, then you can say that task B is dependent on task A. There is a dependency on completion of task A.

You need to consider dependencies as you work through the order of tasks in your plan. Let’s say we are still building that fence that we used as an example when defining project scope. You need to dig post holes before you can put your posts in place. So the task of erecting posts is dependent on the task of digging post holes. You need to have the fence in place before you can paint the fence. So the task of painting is dependent on the task of fencing.

It could be that a task can be dependent on more than one other task or chain of tasks. For example, in the fencing example you might have a group of tasks which are about procuring and preparing material: buying timber, cutting timber, buying hardware and tools. You might have another set of tasks which are about preparing the land, staking out the fence, digging post holes. The set of tasks required to erect the fence is dependent on the tasks required to prepare materials, and the tasks required to prepare the land.

You might also have other dependencies: on other projects (the project you are running to build a gate), or other suppliers (who will provide the fancy hinges you want for your gate), or on particular date (the date you get back from your overseas trip).

As project manager you can also question your dependencies in an attempt to find quicker or better ways of doing things. Did you see that earlier I said you had to put your fence up before you could paint it? Is that true, could it be possible, or even easier, to paint some of the components of the fence before you build it? Questioning your dependencies like this might help you find a better way of doing things.

As a project manager you need to be aware of all dependencies so that you can include them in your plan and have your plan be a more reasonable forecast of reality. If you’re not aware of dependencies you might find your project stuck, waiting for something to complete before you can move on.

So make sure you understand your dependencies, otherwise you will have problems –you can depend on it! (ouch).

You need to consider dependencies as you work through the order of tasks in your plan. Let’s say we are still building that fence that we used as an example when defining project scope. You need to dig post holes before you can put your posts in place. So the task of erecting posts is dependent on the task of digging post holes. You need to have the fence in place before you can paint the fence. So the task of painting is dependent on the task of fencing.

It could be that a task can be dependent on more than one other task or chain of tasks. For example, in the fencing example you might have a group of tasks which are about procuring and preparing material: buying timber, cutting timber, buying hardware and tools. You might have another set of tasks which are about preparing the land, staking out the fence, digging post holes. The set of tasks required to erect the fence is dependent on the tasks required to prepare materials, and the tasks required to prepare the land.

|

| In this example the "Build" tasks are dependent on both the "Design & Prepare" tasks & the "Prepare Boundary" tasks. |

You might also have other dependencies: on other projects (the project you are running to build a gate), or other suppliers (who will provide the fancy hinges you want for your gate), or on particular date (the date you get back from your overseas trip).

As project manager you can also question your dependencies in an attempt to find quicker or better ways of doing things. Did you see that earlier I said you had to put your fence up before you could paint it? Is that true, could it be possible, or even easier, to paint some of the components of the fence before you build it? Questioning your dependencies like this might help you find a better way of doing things.

As a project manager you need to be aware of all dependencies so that you can include them in your plan and have your plan be a more reasonable forecast of reality. If you’re not aware of dependencies you might find your project stuck, waiting for something to complete before you can move on.

So make sure you understand your dependencies, otherwise you will have problems –you can depend on it! (ouch).

Sunday, July 25, 2010

Basic Project Management Definition # 1 – Project Scope

Project management is no stranger to jargon. Project managers use terms which may not be familiar or regularly used by others. Definitions may be useful for you.

Basic Project Management Definition # 1 is “Project Scope”. Your project scope is, put simply, all the things your project will deliver. “Scope” means “extent” or “range”. Your project scope is the extent or range of your project.

One way to think about it is in relation to your work breakdown structure. If you are going to include a task in your project, it is in scope. If you will not complete a task as part of your project, it is out of scope.

For example, if you have a project to build a fence round a garden there will be plenty of tasks in scope including buying materials, digging post holes, and putting up the fence. Tasks unrelated to your project such as tilling the field, or painting the farmhouse are out of scope – they are not part of your project.

Seems easy, but many problems can arise if you are not specific about scope or do not define it clearly. If scope is not clear your customer, whoever has asked for the project, may expect one thing while you expect to deliver another. Let’s think about that fence again – is it in scope for you to paint that fence? Imagine what it will mean to your project, your costs, and the good will with your customer if they assumed you would paint, and you have no intention of painting? Pretty bad, right?

So be clear on what you will deliver. Go back to your work breakdown structure (link) to help you think through exactly what you will deliver – what is in scope. Make sure everyone on the project and your customers know what you have decided – it is better to find out you disagree before work has started than much later. If you find out early you can work through the options, change the scope and cost maybe, and get to a point where all agree what will be delivered.

Project scope: a simple term, but an important one.

Basic Project Management Definition # 1 is “Project Scope”. Your project scope is, put simply, all the things your project will deliver. “Scope” means “extent” or “range”. Your project scope is the extent or range of your project.

One way to think about it is in relation to your work breakdown structure. If you are going to include a task in your project, it is in scope. If you will not complete a task as part of your project, it is out of scope.

For example, if you have a project to build a fence round a garden there will be plenty of tasks in scope including buying materials, digging post holes, and putting up the fence. Tasks unrelated to your project such as tilling the field, or painting the farmhouse are out of scope – they are not part of your project.

Seems easy, but many problems can arise if you are not specific about scope or do not define it clearly. If scope is not clear your customer, whoever has asked for the project, may expect one thing while you expect to deliver another. Let’s think about that fence again – is it in scope for you to paint that fence? Imagine what it will mean to your project, your costs, and the good will with your customer if they assumed you would paint, and you have no intention of painting? Pretty bad, right?

So be clear on what you will deliver. Go back to your work breakdown structure (link) to help you think through exactly what you will deliver – what is in scope. Make sure everyone on the project and your customers know what you have decided – it is better to find out you disagree before work has started than much later. If you find out early you can work through the options, change the scope and cost maybe, and get to a point where all agree what will be delivered.

Project scope: a simple term, but an important one.

Saturday, July 3, 2010

Iterative project planning

So far we have described a number of steps for building a project plan, and they were described in an order that seems logical. First we work out what we are going to deliver, then we work out what tasks we need to do, then we group and order our tasks, then we work out how long each task will take.

It all makes perfect sense. But it probably won’t happen that way. Sure, you’ll work out what you are going to deliver and then think about what steps you need to take…but maybe that will make you re-think what you are going to deliver. When you get to grouping and ordering tasks, you might be reminded of a task that you forgot earlier. While you are estimating the duration of the tasks you may be prompted to re-think the way you ordered your tasks.

Planning is not always the kind of logical, step-by-step process it might initially appear:

Planning is not always the kind of logical, step-by-step process it might initially appear:

- It is an iterative process, which means you will have to keep going back to the beginning and working through the process again, refining as you go.

- There is an element of creativity in planning, using your experience and imagination to predict what is needed and how best to achieve it.

- Each step is likely to help your thinking about other steps.

- You can keep refining each piece of the puzzle until you are happy with it.

For this reason, you might want to consider doing your early stages of planning in a very rough and ready way. Using paper and pencil, or a whiteboard can help to free your thinking in a way that staring at a computer based planning tool (such as MS Project) can’t. You can move faster, think quicker, make notes and scribble things out as you go. Brainstorming with others can also help to speed up your planning. It may be that you will finish your planning in a software tool, but try starting with a method that allows you to plan using broad brush strokes – it can save you a lot of time.

Saturday, June 5, 2010

Identify Key Milestones

There are two definitions for ‘milestone’ (www.dictionary.com) ‘a stone functioning as a milepost’ and ‘a significant event or stage…’. Milestones were used to give travellers information about where they were, indicating how far back to a major town, how far to the next. The traveller could see how far they had travelled, and how far they had to go.

It is no surprise that the word has taken on that second meaning, where an event becomes an opportunity to look back, and look forward. And just as the traveller might use the milestone to make decisions about his journey (do I need to move faster, or spend the night right here) the milestone helps us to make decisions about our project’s progress.

Try to incorporate milestones in to your plan, so that you are able to use them to assess progress as you go. This means you don’t have to wait until the end of the project to see if you are on target. You can pause at your milestone and consider if you had expected to be there earlier, or later, and what you have learned on the way.

Milestones are often formed by your logical groups of tasks. For example, if you have finished all the tasks that are needed to build the foundations of your new house, that could be a significant event, a milestone for your project.

A milestone could be formed by the end of a project stage. For example, completing the design for your new house, could be a significant stage, before the build stage.

A milestone could also be somewhat arbitrary. If you need to build 100 widgets that you will use later in your project you might want to put a milestone half-way through, at 50 widgets, so you can test if you are on track. Or 20% through, 20 widgets.

You can determine what milestones make sense for you. Don’t have so few that you rarely get the opportunity to test your progress, nor so many that they are no longer significant. Use them to reflect, and if necessary re-plan. Use them also to celebrate success, reward yourself and your team, and refresh yourself before moving on the next milestone.

Now, with milestones added to your plan there is just one planning task left – working out what can go wrong.

It is no surprise that the word has taken on that second meaning, where an event becomes an opportunity to look back, and look forward. And just as the traveller might use the milestone to make decisions about his journey (do I need to move faster, or spend the night right here) the milestone helps us to make decisions about our project’s progress.

Try to incorporate milestones in to your plan, so that you are able to use them to assess progress as you go. This means you don’t have to wait until the end of the project to see if you are on target. You can pause at your milestone and consider if you had expected to be there earlier, or later, and what you have learned on the way.

Milestones are often formed by your logical groups of tasks. For example, if you have finished all the tasks that are needed to build the foundations of your new house, that could be a significant event, a milestone for your project.

A milestone could be formed by the end of a project stage. For example, completing the design for your new house, could be a significant stage, before the build stage.

A milestone could also be somewhat arbitrary. If you need to build 100 widgets that you will use later in your project you might want to put a milestone half-way through, at 50 widgets, so you can test if you are on track. Or 20% through, 20 widgets.

You can determine what milestones make sense for you. Don’t have so few that you rarely get the opportunity to test your progress, nor so many that they are no longer significant. Use them to reflect, and if necessary re-plan. Use them also to celebrate success, reward yourself and your team, and refresh yourself before moving on the next milestone.

Now, with milestones added to your plan there is just one planning task left – working out what can go wrong.

Saturday, May 29, 2010

Build Your Plan

At last, you get to build your plan. The basic project management tasks we have described so far have helped you to pull together all the things you need for your plan. You have answered the following questions:

Remember that some tasks, or groups of tasks, can be run at the same time as others. For example, one team could be working on landscaping your garden, while another team renovates your house.

A great way to picture your plan is using a Gantt chart. These charts show the tasks, with a representation of these tasks against a calendar. The simple example below shows a plan for a couple of jobs to improve a house: renovating a living room, and landscaping a garden. You can see there is some logic in the ordering of the tasks – before painting there is preparation of surfaces, before that removing furniture to clear space. You can also see the estimate of duration, and how these add together to give the overall duration of the project. The tasks for renovating the living room take eight days. The tasks for the landscaping also take eight days, but are run in parallel to the living room, so these tasks must be done by a different person or team.

You can also see in this example that the work will be done during the working week, Monday to Friday. Bear in mind that if your project is a personal project then your available time may be in evenings or at weekends. Your plan needs to reflect this – don’t assume you can put in a 40 hour working week on a home project if you still holding down a day job.

Oh, and don’t worry if you don’t have a fancy-schmancy project management tool to build your plan. Use paper and pen, the back of an old envelope, whiteboard, butcher’s paper and crayons. What the plan looks like doesn’t matter. What matters is having a plan that is realistic, that you can commit to, and that will help you deliver whatever it is you’re working towards.

Have fun putting your plan together, and in the next post we will take a look at the plan to identify key milestones you can aim for along the way.

- What will my project deliver?

- What tasks do I need to do?

- What groups of tasks are there?

- In what order should I do these tasks?

- How long will each of these tasks take?

Remember that some tasks, or groups of tasks, can be run at the same time as others. For example, one team could be working on landscaping your garden, while another team renovates your house.

A great way to picture your plan is using a Gantt chart. These charts show the tasks, with a representation of these tasks against a calendar. The simple example below shows a plan for a couple of jobs to improve a house: renovating a living room, and landscaping a garden. You can see there is some logic in the ordering of the tasks – before painting there is preparation of surfaces, before that removing furniture to clear space. You can also see the estimate of duration, and how these add together to give the overall duration of the project. The tasks for renovating the living room take eight days. The tasks for the landscaping also take eight days, but are run in parallel to the living room, so these tasks must be done by a different person or team.

You can also see in this example that the work will be done during the working week, Monday to Friday. Bear in mind that if your project is a personal project then your available time may be in evenings or at weekends. Your plan needs to reflect this – don’t assume you can put in a 40 hour working week on a home project if you still holding down a day job.

Oh, and don’t worry if you don’t have a fancy-schmancy project management tool to build your plan. Use paper and pen, the back of an old envelope, whiteboard, butcher’s paper and crayons. What the plan looks like doesn’t matter. What matters is having a plan that is realistic, that you can commit to, and that will help you deliver whatever it is you’re working towards.

Have fun putting your plan together, and in the next post we will take a look at the plan to identify key milestones you can aim for along the way.

Saturday, May 22, 2010

Estimate the effort required to complete each task

If you’ve followed the posts so far you are well on the way to creating your project plan. You have a list of tasks needed to deliver the outcomes of your project. You put your tasks into logical groupings. Then you arranged your tasks in a logical order to show which tasks must be completed before others can begin.

Now you need to estimate how long each of those tasks will take. At this stage it is only an estimate – you can’t know for sure how long something will take unless you can foresee the future. You won’t know, for example, what problems might slow you down, or what you will have to do to fix these problems. Estimation can also be difficult if you are doing work that you have not done before, so you have no experience to base your estimate on. Estimation can also be difficult if you are doing creative work, such as design – who knows how long it will take to create a design that you or your client is comfortable with? You might also need to know who is going to do the work – someone with experience will work faster, and make less errors, than someone without experience.

In short, estimation is fraught with difficulties. No wonder then that this can cause problems with projects. Under-estimates can mean the project team is working against difficult or impossible targets. It can mean that your project is under-funded – for example if you asked for costs to cover 100 days, but should have asked for 200 days. Impossible timeframes and lack of funds will cause stress both for you and your team.

So, what can you do to improve your estimating?

For now, while we work through the first version of your first project plan I suggest you keep it simple.

Think about your first task, and work out how long you think it would take you. You need to consider how much time you are devoting to your project. Let’s say you are building a fence. If you think this would take you five days to build, but you can only do this at weekends, then it is going to take you two and a half weekends. That’s three weeks – not one.

Use your experience. If you have built fences before you will have a better understanding of the effort and problems involved. Compare the fence you are building now to the fences you have built before. What is the same, what is different? What does that mean for your estimate?

Use the work breakdown structure to visualise each task. A ‘dry run’ of your project may help you to estimate. How long will it take to dig post holes? How long will it take to procure and transport the timber? How long will it take to set the posts?

When will you be finished? This is about being clear on the scope of your project. Are you finished when the fence is built? Or when it is painted or treated? Or when you have painted a second coat? If you are not completely clear on scope your estimate will be way out – and it could be that your project expenses are way out too. If you underestimate cost, you can lose profit.

Now, you have ordered and grouped tasks, and you have estimates. All you need to do now is build your plan.

Now you need to estimate how long each of those tasks will take. At this stage it is only an estimate – you can’t know for sure how long something will take unless you can foresee the future. You won’t know, for example, what problems might slow you down, or what you will have to do to fix these problems. Estimation can also be difficult if you are doing work that you have not done before, so you have no experience to base your estimate on. Estimation can also be difficult if you are doing creative work, such as design – who knows how long it will take to create a design that you or your client is comfortable with? You might also need to know who is going to do the work – someone with experience will work faster, and make less errors, than someone without experience.

In short, estimation is fraught with difficulties. No wonder then that this can cause problems with projects. Under-estimates can mean the project team is working against difficult or impossible targets. It can mean that your project is under-funded – for example if you asked for costs to cover 100 days, but should have asked for 200 days. Impossible timeframes and lack of funds will cause stress both for you and your team.

So, what can you do to improve your estimating?

For now, while we work through the first version of your first project plan I suggest you keep it simple.

Think about your first task, and work out how long you think it would take you. You need to consider how much time you are devoting to your project. Let’s say you are building a fence. If you think this would take you five days to build, but you can only do this at weekends, then it is going to take you two and a half weekends. That’s three weeks – not one.

Use your experience. If you have built fences before you will have a better understanding of the effort and problems involved. Compare the fence you are building now to the fences you have built before. What is the same, what is different? What does that mean for your estimate?

Use the work breakdown structure to visualise each task. A ‘dry run’ of your project may help you to estimate. How long will it take to dig post holes? How long will it take to procure and transport the timber? How long will it take to set the posts?

When will you be finished? This is about being clear on the scope of your project. Are you finished when the fence is built? Or when it is painted or treated? Or when you have painted a second coat? If you are not completely clear on scope your estimate will be way out – and it could be that your project expenses are way out too. If you underestimate cost, you can lose profit.

Now, you have ordered and grouped tasks, and you have estimates. All you need to do now is build your plan.

Saturday, April 24, 2010

Arrange your tasks in order

So by now you should have an idea of all the things your project is going to deliver. You should also have a list of the tasks you need to complete to deliver these things. You have also put your tasks into natural groupings. The next basic project management step is to think about the order these tasks will be completed in.

Knowing the order will help to translate your list of tasks from a “To Do” list to a plan. Knowing the order means you know which tasks you will complete first. And then when you have finished that task, which task comes next, and so on. The plan guides you through each task, one by one, until you reach the end of the project. Having this ordered plan makes you efficient. When you have time for your project you don’t need to wonder “What next?” – the plan will tell you this.

So what things might you consider when you put your tasks in order?

Some tasks simply cannot be completed before others are completed. For example, you can’t build the walls on your new house, until you have completed the foundations. You can’t tile until you have prepared the wall. You’ can’t knit a sweater until you have bought the wool.

There may be some tasks that need to be done early because there is a long lead time. If your tiles need to be shipped in from overseas you might complete the task of ordering them early, so they are delivered by the time you are ready to tile.

It may be that you only have the resources to do a task at a particular time. For example, you can borrow your friends van to help you pick up building materials, but it is available one weekend only.

Consider also that not all tasks need to be ordered sequentially, one after the other. You may start some tasks at the same time as others, especially when you have a team of people who can all work on different tasks. You don’t need to wait for your small business to start up before you start working on your business plan.

Ordering your tasks is about putting them in a logical sequence, but also, as you can see from the examples, you may start to think about scheduling them against a calendar. The next step of basic project planning which will really help you to schedule your plan is to estimate the effort required to complete each task.

Knowing the order will help to translate your list of tasks from a “To Do” list to a plan. Knowing the order means you know which tasks you will complete first. And then when you have finished that task, which task comes next, and so on. The plan guides you through each task, one by one, until you reach the end of the project. Having this ordered plan makes you efficient. When you have time for your project you don’t need to wonder “What next?” – the plan will tell you this.

So what things might you consider when you put your tasks in order?

Some tasks simply cannot be completed before others are completed. For example, you can’t build the walls on your new house, until you have completed the foundations. You can’t tile until you have prepared the wall. You’ can’t knit a sweater until you have bought the wool.

There may be some tasks that need to be done early because there is a long lead time. If your tiles need to be shipped in from overseas you might complete the task of ordering them early, so they are delivered by the time you are ready to tile.

It may be that you only have the resources to do a task at a particular time. For example, you can borrow your friends van to help you pick up building materials, but it is available one weekend only.

Consider also that not all tasks need to be ordered sequentially, one after the other. You may start some tasks at the same time as others, especially when you have a team of people who can all work on different tasks. You don’t need to wait for your small business to start up before you start working on your business plan.

Ordering your tasks is about putting them in a logical sequence, but also, as you can see from the examples, you may start to think about scheduling them against a calendar. The next step of basic project planning which will really help you to schedule your plan is to estimate the effort required to complete each task.

Sunday, April 11, 2010

Group similar tasks together

I recommended in an earlier post that the first thing you need to do when planning a project is to list every task. What are all the things your project will create and what are the things you need to do to create them?

This list is a great start, and it helps to keep it simple at this stage and just let your mind roam freely over what might need to be done. When you have this list your next step will be to start making it into a plan.

Firstly, group together things which are similar. Things you are going to make or do which fit together naturally. For example, if your project was to renovate a room in your house you might group together all those things you need to do before you get started: maybe you need to buy tools, paint, or other materials. You might group together all the things you need to do to prepare the room: clearing out furniture, stripping wallpaper, sanding woodwork. You might then group together all the things you need to do for the renovation itself: painting, repairing.

Let's look at another example of grouping tasks. If you were setting up a new business you might group together all those things you need to do before you get started: agreeing a company structure, finding an accountant, market research, building a pricing model. All of those things would help you to put together a business plan. So, your first group of tasks is based on creating the business plan. Another group of tasks might be all the things you need to do from the moment you create your business: setting up shop, marketing, manufacturing. Another group might be all the things you need to do to market your business: buiding a web-site, advertising, networking.

With each of these examples the groups of tasks all aim towards delivering something to your project. It might be an empty room ready for painting, or it might be a marketing plan put in place.

Groups of tasks like these are often used in project management to provide a target to aim for, or a 'milestone'. Completing all the tasks in a group, which often means actually delivering something, can provide a great sense of achievement. That's another great reason to put some thought into your groups. Try to design groups of work that not only fit together naturally, but allow you to complete something early in your project.

Of course you can have groups within groups. In our new business example above there is a group of tasks for marketing which are part of the group of tasks for kicking off the business. This is also a way of making it easier for yourself to get early wins.

So far we have listed the tasks we need to complete for our project, and we have grouped tasks into natural bundles that will often deliver something to our project. The next step of building up our work breakdown structure, or project plan, is to think about the order in which we complete each of the tasks.

This list is a great start, and it helps to keep it simple at this stage and just let your mind roam freely over what might need to be done. When you have this list your next step will be to start making it into a plan.

Firstly, group together things which are similar. Things you are going to make or do which fit together naturally. For example, if your project was to renovate a room in your house you might group together all those things you need to do before you get started: maybe you need to buy tools, paint, or other materials. You might group together all the things you need to do to prepare the room: clearing out furniture, stripping wallpaper, sanding woodwork. You might then group together all the things you need to do for the renovation itself: painting, repairing.

Let's look at another example of grouping tasks. If you were setting up a new business you might group together all those things you need to do before you get started: agreeing a company structure, finding an accountant, market research, building a pricing model. All of those things would help you to put together a business plan. So, your first group of tasks is based on creating the business plan. Another group of tasks might be all the things you need to do from the moment you create your business: setting up shop, marketing, manufacturing. Another group might be all the things you need to do to market your business: buiding a web-site, advertising, networking.

With each of these examples the groups of tasks all aim towards delivering something to your project. It might be an empty room ready for painting, or it might be a marketing plan put in place.

Groups of tasks like these are often used in project management to provide a target to aim for, or a 'milestone'. Completing all the tasks in a group, which often means actually delivering something, can provide a great sense of achievement. That's another great reason to put some thought into your groups. Try to design groups of work that not only fit together naturally, but allow you to complete something early in your project.

Of course you can have groups within groups. In our new business example above there is a group of tasks for marketing which are part of the group of tasks for kicking off the business. This is also a way of making it easier for yourself to get early wins.

So far we have listed the tasks we need to complete for our project, and we have grouped tasks into natural bundles that will often deliver something to our project. The next step of building up our work breakdown structure, or project plan, is to think about the order in which we complete each of the tasks.

Saturday, January 30, 2010

Keep it Simple

Project management (PM) can be a huge, complex, but powerful tool. You can plan and manage massive projects like building a bridge, or a rail line, or sending a satellite into orbit. To run this level of project you would need to plan, schedule, cost and re-plan until your plan was perfect. If you are sending someone into space, or building a rail line, don’t rely on this blog!

This blog is about basic project management. It is about using the fundamental, basic techniques of PM to help get you achieve your personal projects more efficiently. It is about delivering your work projects efficiently too, especially when you want to see results quickly. You can keep avoid over-engineering your work but still use project management techniques to help you deliver.

Let’s use an example. You have been asked, let’s say, to facilitate a small training course at your workplace. It may not make sense to build a complex project plan for this, but it would make sense to at least think of all the things you need to deliver this project, and all the tasks you need to complete. You might need to invite a speaker, book a room, arrange catering, arrange IT resources or stationery, send invites, print materials…You can use a work breakdown structure to help you quickly determine everything you need, what you need to do to deliver these, and to work on your priorities.

You do not need to agonise over the plan, or make it complex. You can keep it simple. The ability to ‘keep it simple’ is one of the ‘soft’ skills I recommend in Project Life for anyone managing a project. If you can simplify things, instead of adding complexity, you will make things easier for yourself, your team, and your stakeholders – the people you are managing the project for.

This blog is about basic project management. It is about using the fundamental, basic techniques of PM to help get you achieve your personal projects more efficiently. It is about delivering your work projects efficiently too, especially when you want to see results quickly. You can keep avoid over-engineering your work but still use project management techniques to help you deliver.

Let’s use an example. You have been asked, let’s say, to facilitate a small training course at your workplace. It may not make sense to build a complex project plan for this, but it would make sense to at least think of all the things you need to deliver this project, and all the tasks you need to complete. You might need to invite a speaker, book a room, arrange catering, arrange IT resources or stationery, send invites, print materials…You can use a work breakdown structure to help you quickly determine everything you need, what you need to do to deliver these, and to work on your priorities.

You do not need to agonise over the plan, or make it complex. You can keep it simple. The ability to ‘keep it simple’ is one of the ‘soft’ skills I recommend in Project Life for anyone managing a project. If you can simplify things, instead of adding complexity, you will make things easier for yourself, your team, and your stakeholders – the people you are managing the project for.

Saturday, January 23, 2010

List every task

You can’t get more basic in basic project management than defining your work breakdown structure. It’s a fundamental part of planning your project. But before we look at what it can do for you, let’s pull that bit of jargon apart and say what it is: it's a list of all the things you need to do to complete your project.

That’s all it is. A “To do” list.

Put into your list everything you think you need to do. The list might include tasks which help prepare for your project, such as buying materials or planning. It should include all the tasks you need to do complete your project, maybe building, writing, creating. Your list should also contain all the things you need to do to finish your project.

When you start making this list don't worry too much about formatting it, or ordering it. There is more you can do later to turn your list into a plan. For now just list every task that comes to mind. Later we will think about grouping similar tasks together and putting our tasks in order

The following is an extract from Project Life which explains the benefits to you of building your work breakdown structure when planning a project:

My first step in building the plan is to identify smaller jobs that make up the whole project. I literally break down the work into component tasks. Why do we go to the trouble of breaking down the project into these component tasks? Why not just say “Renovate bathroom”? I know roughly what the tasks are, so why write them down separately?

Because seeing each task as a separate item forces me to think about each step I need to take. I can take each of those steps in my mind and think about the problems I might encounter. Thinking through each step in detail allows me to foresee and prepare for work, which otherwise I am simply going to stumble into, perhaps unprepared and without the right tools. I can see steps that I might miss out or not consider properly if I thought only at project level. I can think through things that might go wrong, or might be difficult for me. If I am able to spot these risks, then I can also think about adding other tasks that help me to deal with those risks.

Having broken down the project into these component tasks, and thought about the problems that might arise, I can estimate more accurately how long each step might take. Estimating how long each step takes, and adding up each of these estimates, is going to be much more accurate than estimating at project level. My estimate for ‘renovate bathroom’ can be little more than a guess, but my estimate for “paint ceiling” has some chance of being more realistic.

Seeing each step separately also allows me to put the steps into a logical sequence. It allows me to spot dependencies between tasks. I know that before I can put in new tiles I need to remove the old tiles.

I can also group related tasks together. For example, there are a number of things I need to buy up front. There are a number of things I need to do to prepare the bathroom before tiling. This grouping gives me a sense of the main sets of tasks within the project, and also helps me to think through if I have included all such tasks.

Having the project split into smaller steps also allows me to think about who can do the work. Perhaps I can give some tasks to other people, and ask them to do the work. I will get a plumber to do some of the key tasks, for which I do not have the right skills or experience.

Formulating a plan with step after organised step allows me to get an accurate picture of what I need to do to get to the end of the project. It gives me a ‘rich’ picture, saturated with detail, which gives me the ability to visualise more clearly what is involved in getting to the end of the project: to having a renovated bathroom.

Finally, when I start work, the plan helps me to focus on one task at a time, not the whole project. I can see that to get to the end of the project I need to finish step one first, then move onto step two, then step three. Without this rich picture I might not work as logically or efficiently.

That’s all it is. A “To do” list.

Put into your list everything you think you need to do. The list might include tasks which help prepare for your project, such as buying materials or planning. It should include all the tasks you need to do complete your project, maybe building, writing, creating. Your list should also contain all the things you need to do to finish your project.

When you start making this list don't worry too much about formatting it, or ordering it. There is more you can do later to turn your list into a plan. For now just list every task that comes to mind. Later we will think about grouping similar tasks together and putting our tasks in order

The following is an extract from Project Life which explains the benefits to you of building your work breakdown structure when planning a project:

My first step in building the plan is to identify smaller jobs that make up the whole project. I literally break down the work into component tasks. Why do we go to the trouble of breaking down the project into these component tasks? Why not just say “Renovate bathroom”? I know roughly what the tasks are, so why write them down separately?

Because seeing each task as a separate item forces me to think about each step I need to take. I can take each of those steps in my mind and think about the problems I might encounter. Thinking through each step in detail allows me to foresee and prepare for work, which otherwise I am simply going to stumble into, perhaps unprepared and without the right tools. I can see steps that I might miss out or not consider properly if I thought only at project level. I can think through things that might go wrong, or might be difficult for me. If I am able to spot these risks, then I can also think about adding other tasks that help me to deal with those risks.

Having broken down the project into these component tasks, and thought about the problems that might arise, I can estimate more accurately how long each step might take. Estimating how long each step takes, and adding up each of these estimates, is going to be much more accurate than estimating at project level. My estimate for ‘renovate bathroom’ can be little more than a guess, but my estimate for “paint ceiling” has some chance of being more realistic.

Seeing each step separately also allows me to put the steps into a logical sequence. It allows me to spot dependencies between tasks. I know that before I can put in new tiles I need to remove the old tiles.

I can also group related tasks together. For example, there are a number of things I need to buy up front. There are a number of things I need to do to prepare the bathroom before tiling. This grouping gives me a sense of the main sets of tasks within the project, and also helps me to think through if I have included all such tasks.

Having the project split into smaller steps also allows me to think about who can do the work. Perhaps I can give some tasks to other people, and ask them to do the work. I will get a plumber to do some of the key tasks, for which I do not have the right skills or experience.

Formulating a plan with step after organised step allows me to get an accurate picture of what I need to do to get to the end of the project. It gives me a ‘rich’ picture, saturated with detail, which gives me the ability to visualise more clearly what is involved in getting to the end of the project: to having a renovated bathroom.

Finally, when I start work, the plan helps me to focus on one task at a time, not the whole project. I can see that to get to the end of the project I need to finish step one first, then move onto step two, then step three. Without this rich picture I might not work as logically or efficiently.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)